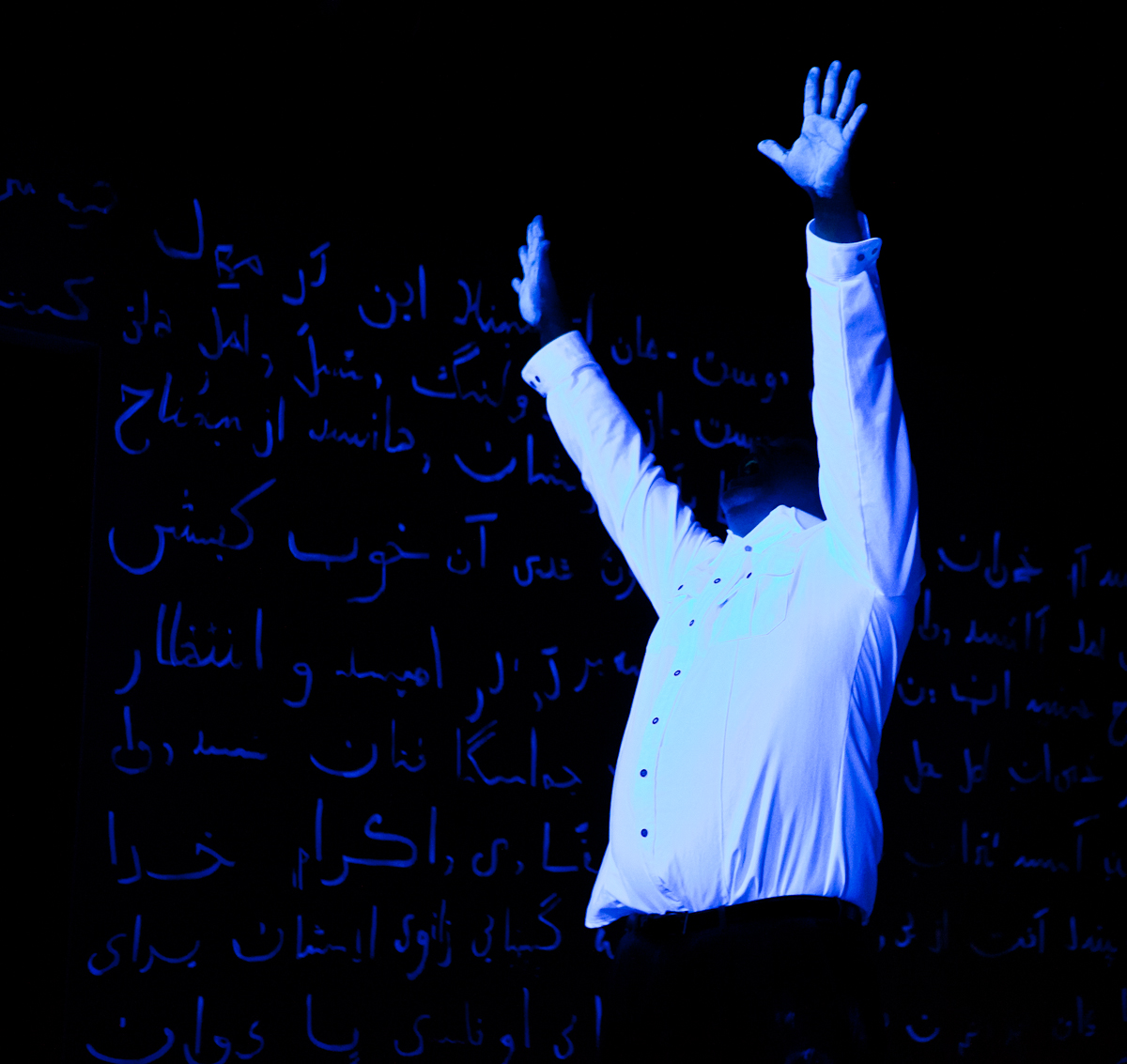

End Gaze was born out of an evening of playing Surrealist Games at Timothy Beyer’s home. A question emerged: how to consciously lose control, tie one’s own hands, allow the subconscious to dance, all while watching…is it possible?

I settled on Automatic Writing.

But writing music is a slow process. How to do it?

I decided I would not look back. Only forward. I would gaze towards the end. I scribbled gestures quickly, allowing only minimal editing. The usual composerly question—“How does this part relate to that?”—fell into the background.

A new idea begins late in the piece. It doesn’t seem to belong. But it does, and I continue, leaning into the now and just ahead. I write material without knowing where it will go. It’s not that I learn to trust that it will all make sense, it’s that I stop requiring it to.

Yet, my brain connects dots. Even these different, disparate ideas line up, not in a “making sense” kind of way, but in some kind of way.

I also gaze at different endings. The fraying of democracy. A loneliness amplified by a pandemic and an end to our collective sense of bodily safety. I gaze at fragility. But also at light. And heroism. And darkness.