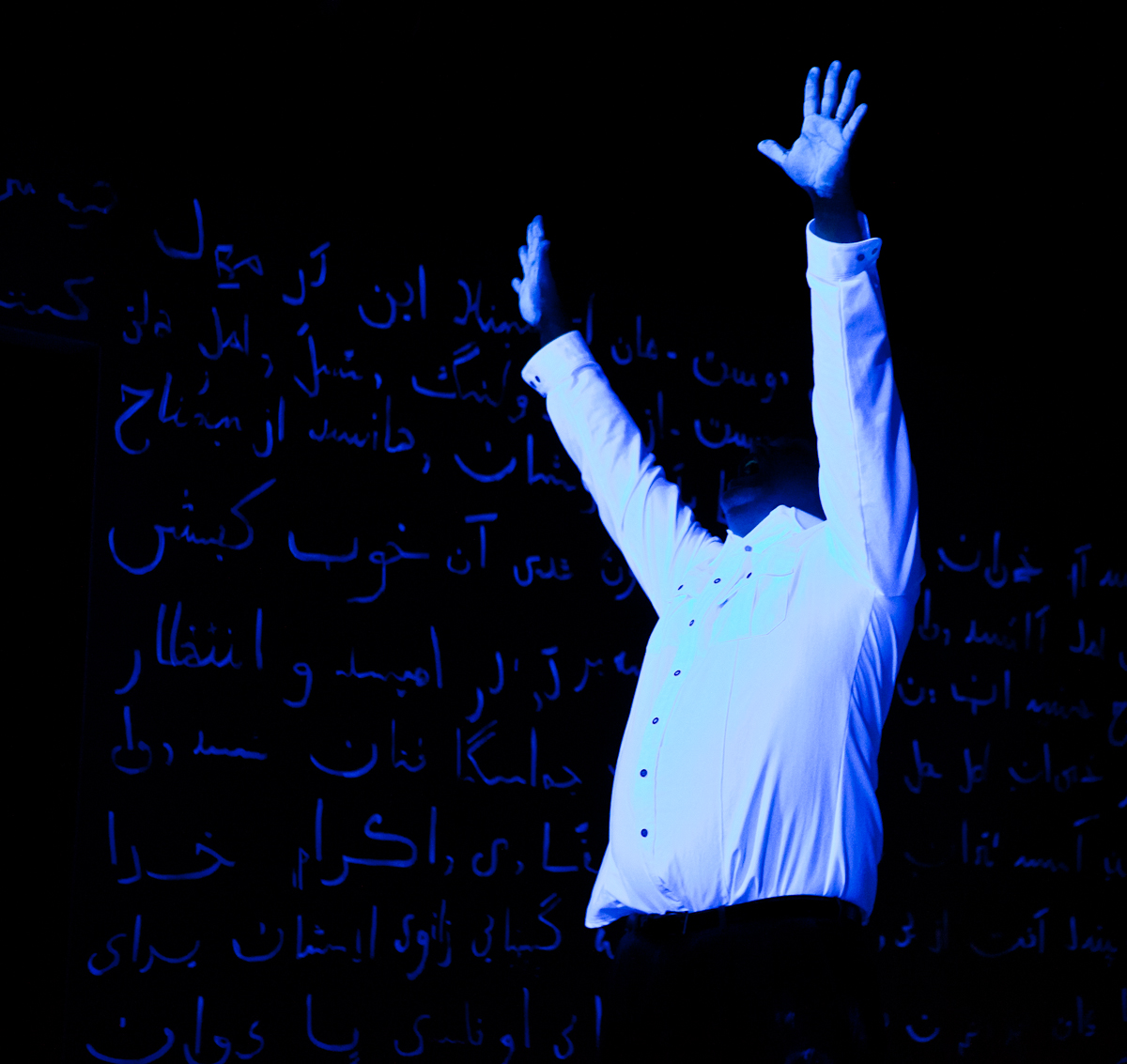

Giver of Light is a chamber opera based on the life of the 13th-century Sufi mystic poet Rumi. Rumi’s life story is an extraordinary tale of transformation, one which is as relevant today as it was nearly one thousand years ago.

As the myth goes, Rumi began as a respected scholar and was transformed when Shams of Tabriz, a wandering mystic, walked into town and challenged Rumi to transcend his book learning and taste the waters of existence through direct experience. Rumi was intensely drawn to Shams, and their electric connection was one of the forces that changed Rumi into the mystical poet we know and love today. The other main catalyzing ingredient was grief: it is rumored that certain townspeople were jealous of Rumi’s relationship with Shams, and one of them—perhaps even one of Rumi’s sons—may have murdered Shams. In any case, we know that Shams disappeared, and Rumi’s longing for the absent Shams inspired Rumi to begin creating poetry.

In deciding on a subject matter for my chamber opera, I felt that Rumi’s life story was particularly relevant for this time. We are living in an age of soundbites and cool detachment in which we cultivate our identities through social media alone in our rooms. We are more “connected” than ever before and perhaps more lonely. I can only imagine that people today must relate to Rumi’s longing for intensity. I certainly do.

My idea in writing the libretto for this opera was to translate the main events of Rumi’s story into a modern tale set somewhere in the American Midwest. In Giver of Light, Rumi is John, a white male in his forties who “has it all,” a beautiful wife (Elena), child (Brian), and a good job selling hybrid cars. He is conscientious and well respected. He does yoga and recycles. But he feels empty on the inside and when he encounters Darren, a mystic who drives Brian’s school bus, John’s world is turned upside down.

In working on this piece, I attempted to create two distinct musical spaces: one which represents “normal,” “outer” life, and is generally rhythmic and conversational in tone, and another space which represents the “inner” life of John and Darren and that is more abstract and sonically strange. The electronics, composed by Anıl Çamcı, are primarily heard in the second type of music to create a sense of space and ritual during the meditative scenes. In this way I was inspired by Jonathan Harvey’s point of view, in seeing electronics as a way of “expanding a listener’s consciousness outside the normal world of instruments.”*

The main characters of this opera are everyman and everywoman, archetypes that are general enough that we may see our own reflections in them. I hope that as the opera unfolds we as audience members have the chance to experience this drama through John, Elena, Darren, and Brian’s eyes. I believe that Rumi’s longings were and are universal, and it is my hope that this piece might allow Rumi’s experiences to resonate in us here and now.

*Harvey, Jonathan. “Composer in Focus: Jonathan Harvey- Interview.” Composer’s Notebook Quarterly. Trigueros, Francisco Castillo, Ed. Dec., 2007. Web. May 19, 2013.